The False Dichotomy of Open vs Closed Kinetic Chain

Open kinetic chain (OKC) vs closed kinetic chain (CKC); we have heard it all before. There are arguments that OKC is more dangerous (it’s not) or that it puts more stress on the patellofemoral joint (yeah, sometimes it can, as does valgus but that is not inherently “good” or “bad”). The argument that I am going to discuss today relates more to whether or not one type of exercise is more “functional” or not. Why? Because this is the argument that pisses me off the most which makes my blood pressure rise and my doctor says that I need to find a good outlet for my anger issues or something.

First, this is a false dichotomy which casts these two things as polar opposites that do not overlap in any way. Function is a continuum that goes all the way to the task itself. But we must remember, as it has been said by many people before me:

The most functional activity IS the activity itself…

Everything else is just a simulation at best. Even the most “functional” thing we do in the clinic or weight room is not really all that functional. Much of this has to do with the mental focus of the athlete but there is also the question relating to whether or not there is enough capacity, or “foundational strength”, to even do the task (I have written about these ideas before as well both here and here).

But let’s assume that we really are trying to simulate the desired task at hand, as closely as possible, right in the clinic. We are trying to train in a way that is targeted directly at the “root” deficit. The most common justification of CKC over OKC, specifically regarding ACL injury, is:

The foot is in contact with the ground during the injury and during other moments in their sport. Therefore, it is a CKC task and CKC exercises will be the closest simulation.

Ok. I see what you are saying. But is that REALLY what you care about? Whether or not the foot is in contact with the ground? Is that what makes something “functional”? Foot position? Or is it something else?

What are the “kinetic chains”?

The very first thing that we need to understand here is that this OKC vs CKC dichotomy is not actually a physics/engineering thing. In 1955 Arthur Steindler first introduced these terms in Kinesiology of the Human Body Under Normal and Pathological Conditions. It specifically relates ONLY to exercises. If the terminal segment met significant resistance, it was deemed “closed”; if the terminal segment was free to move, it was deemed “open”.

Now, let’s give credit where credit is due. Arthur Steindler was brilliant and a HUGE contributor to orthopedic medicine. This view that constraining the terminal segment has an effect on the function of a nearby joint is very important to understand. But there is a problem here. In isolation it is an extremely narrow and poorly defined construct. This has been pointed out in our own literature in the past but our profession still refuses to abandon the concept.

In isolation “open” vs “closed” is more of a kinematic description, not so much a kinetic description (actually “closed” would mean BOTH ends are blocked so technically it barely describes any exercise very clearly, even kinematically). How force enters and moves through the system is ultimately the thing we really care about.

Wait. I’m really sorry, this is getting a little abstract. Let’s get away from all these technicalities and use some real world examples.

What exactly are we trying to do here?

Actually, there is a lot of variation of what can happen at the knee when the foot is in contact with the ground. As I just mentioned, what happens at the knee joint IS affected by such a constraint as ground contact. HOWEVER, what really matters to the knee is what is ACTUALLY happening at the knee joint itself. And that is dictated by how force enters and moves through the system.

So let’s look at one of the most functional movements in sport and the moment when most non-contact ACL injuries occur: Cutting. A simple definition of cutting would be changing the direction of one’s momentum quickly. You have a head of steam going in one direction, now you have to stop that momentum (deceleration) and generate new momentum (acceleration) in another direction. The problem usually occurs during the deceleration. So let’s look at what that means.

“Step-Back” drill with PVC “gate” for environmental/visual constraint

Image property of Erik Meira

This is an image of one of my athletes doing what we call the “Step-Back”. They must accelerate forward, plant on one foot on their toes, and thrust directly backwards keeping hips low and head up. (In this image there is also a PVC “gate” that we use to provide an environmental/visual constraint to prevent hip/trunk flexion but don’t worry about that in this post.) Try having a quad deficient patient attempt this then compare to the opposite side, just for shits and giggles.

We are using this task as our reference example of function (relates closely to cutting demands) so let’s see what is going on with the major forces at play.

“Step-Back” drill with oversimplified gross force vectors

Image property of Erik Meira

So you can see that there is a large amount of energy moving forward (blue arrow above). When the foot makes contact with the ground to initiate the “Step-Back”, the lower extremity must generate an equal and opposite amount of force (red arrow above) via deceleration to stop that momentum before redirecting the athlete’s mass backward.

Now, let’s go to our exercises and see what simulates this force the most closely, in other words what is most “functional”, in this case. First thing we notice about this task is that it is single leg with the foot on the ground. That’s CKC right? So let’s look at the single leg squat, the gold standard CKC exercise, and compare/contrast forces.

Comparison of Single-Leg Squat forces to “Step-Back” forces

Single-Leg Squat image used by permission of Patrick Corrigan at the University of Delaware edited by Erik Meira

Ah crap. That doesn’t simulate those forces at all. Here we expose one of the biggest yet most common mistakes that a physical therapist can make:

Just because an exercise LOOKS LIKE the task, does not mean it RECREATES THE DEMANDS of the task

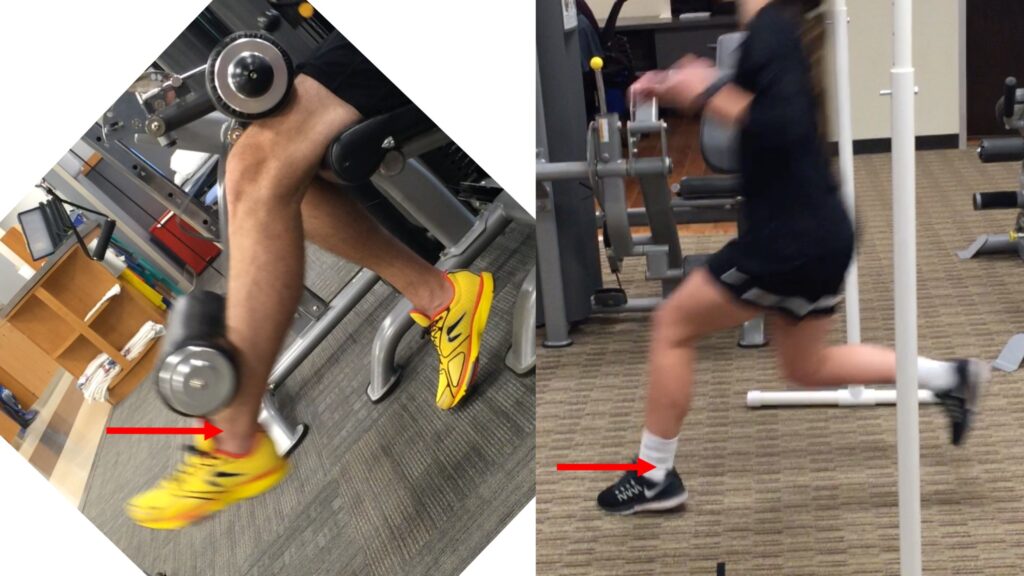

Instead let’s look at a leg extension, the quintessential OKC exercise, and compare/contrast the forces.

Comparison of Leg Extension forces to “Step-Back” forces

Leg Extension image used by permission of Patrick Corrigan at University of Delaware edited by Erik Meira

Much better, but in case you can’t see that similarity, let’s rotate one of the images.

Rotated version of Leg Extension forces to “Step-Back” forces

Leg Extension image used by permission of Patrick Corrigan at the University of Delaware edited by Erik Meira

Is this the EXACT force profile as real-world cutting with all of its dynamic complexity? No, but it is MUCH CLOSER to the desired force profile than the single leg squat. Not that the single leg squat does nothing (we use them a lot) but it is LESS “functional” than the leg extension from this perspective. So the opposite of the big mistake I mentioned above is this simple truth:

Just because an exercise DOESN’T LOOK LIKE the task, does not mean it DOESN’T RECREATE THE DEMANDS of the task

As I mentioned earlier, this OKC vs CKC “debate” is a completely false dichotomy. Weirdly, the forces at the knee produced by this “closed kinetic chain” activity are better recreated by an “open kinetic chain” exercise. Why? Because this OKC/CKC construct is too poorly defined to be very useful by itself.

But the MOST functional exercise would be the “Step-Back”, right?

Sure, but that puts a HUGE demand on the quadriceps; a muscle that is likely very weak in an athlete recovering from knee surgery. We don’t train the quadriceps by putting a load that is way beyond its capabilities. Instead we train the quadriceps at its optimal loads and we can fine tune those loads much easier with a leg extension machine. There is evidence that these patients with quad weakness will, over time, learn to master your “functional” tests (hops, jumps, cuts, etc) by using their hips. Strong hips are great, but not if it is a result of sacrificed knee strength.

Before you start asking the quadriceps to function at a very high level during a complex movement, make sure it can function at even a reasonable level in the simplest movement. Personally, I only bring in drills like the “Step-Back” after their quad function reaches a certain threshold.

In summary…

- I need to find a good outlet for my anger issues or something

- Let’s stop using “open kinetic chain” and “closed kinetic chain” – they are not useful

- How force enters and moves through the system is ultimately the thing we really care about

- Just because an exercise LOOKS LIKE the task, does not mean it RECREATES THE DEMANDS of the task

- Just because an exercise DOESN’T LOOK LIKE the task, does not mean it DOESN’T RECREATE THE DEMANDS of the task

- You should really read that old open source JOSPT article from 1994 on all this weirdness by Gary Smidt

P.S. I teach a weekend course that covers all of these things. Just saying…

Special thanks to Rich Willy for helping me get those images that Pat provided.